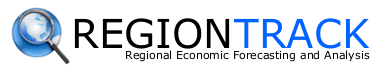

The short answer is that the Oklahoma economy remains VERY sensitive to oil and gas activity. A useful way to illustrate the link is to…

The Devil is in the Detail: RegionTrack Response to Blog Post by Jerry Johnson and Michael Clingman

“”The devil is in the detail” is an idiom that refers to a catch or mysterious element hidden in the details,[1] meaning that something might seem simple at a first look but will take more time and effort to complete than expected [2] and derives from the earlier phrase, “God is in the detail” expressing the idea that whatever one does should be done thoroughly; i.e. details are important.”

Source: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_devil_is_in_the_detail

Jerry Johnson and Michael Clingman take issue with a recent published estimate by RegionTrack economists of the direct tax revenue paid by the oil and gas industry in Oklahoma (see: Economic Impact of the Oil & Gas Industry On Oklahoma, September 2016, Oklahoma State Chamber Research Foundation, http://okoga.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/SCRF-Economic-Impact-of-Oil-and-Gas-Industry-on-OK-2016-Study.pdf).

Their blog post is provocatively titled “Gross production tax: Lies, damn lies and estimates” (https://nondoc.com/2017/05/04/gross-production-tax-lies/) and questions some of the results in the report.

While we always appreciate well-reasoned and thoughtful criticism of our work, their blog post falls a bit short of this objective. Instead, it illustrates the clear line that must always be drawn between economic research and political activism when considering state tax policy changes. Because the Devil is always in the detail, and because it will be helpful for state policymakers who are charged with the difficult task of setting state tax policy, we provide an in-depth analysis of their blog post below.

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman begin by asking why we use estimates when ‘actual’ data exist for corporate income tax? We always chuckle a bit when someone talks about ‘actual’ data. But it seems like a good question, right? Well, the answer is because ‘actual’ corporate tax receipts are never known with any degree of certainty until years after the fact. ‘Actual’ numbers are not immediately available because losses experienced by corporations are regularly carried backward and forward to offset income earned in past and future years. The ongoing restatement of corporate tax liability is not a minor point. Oil and gas corporate income tax payments have been much lower than expected in recent years because of the losses experienced by the industry as crude oil and natural gas prices collapsed and corporate tax payments in prior years (and possibly future years) are offset. A better question they should be asking instead is: Which will provide a better estimate of current corporate income tax payments? The current estimate on the books or a model based on historical payments? In short, Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman are attempting to evaluate an estimate that was based solely on the historical data available at the time by using data that can only be known after the fact. They are also ignoring the complex reporting and timing issues surrounding corporate tax receipts and have not stated whether the numbers they present are calculated based on the year the tax liability was incurred or the year of final filing. This might seem like nothing more than a debate over details, but it goes far deeper than that. It mischaracterizes the real policy issues underlying tax policy in the state. Those who have closely followed the issues faced by the Tax Commission in forecasting corporate tax receipts the past several years understand that ‘actuals’ are not ‘actuals’ until far down the road. To suggest otherwise is simply misleading. Which is why we label our estimates as ‘estimates’ and described the approach used in forming the estimates.

Moreover, their characterization of the methodology we used to estimate corporate income taxes is not only grossly misleading but simply wrong. Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman lifted a direct quote from our report to describe the approach but edited the original language in the process. Here is the ‘actual’ direct quote from the report: “The 22% estimate is derived from a quarterly regression model linking Oklahoma corporate tax receipts to the market value of oil and gas production and the profitability and tax payments of oil and gas firms nationally.”

In simplest terms, our model provides an estimate of the historical relationship between corporate tax revenue received in Oklahoma as it is related to the value of oil and gas production in the state and given the relationship state corporate tax receipts have with changes in both the corporate profitability of the U.S. mining sector and corporate tax payments made by the U.S. mining sector. The use of U.S. data assumes that the financial health of the U.S. oil and gas industry is a good proxy for the financial health of the state’s oil and gas industry. We believe this remains a good assumption. Specifically, the model provides an estimate of the average expected state corporate tax receipts over time given the effect of the value of oil and gas production and oil and gas industry profitability and tax payments. It is not attempting to predict the ever-changing value associated with any single year. In addition, it does not suggest in any way a certain level of taxation that is fair or equitable, a conclusion that seems to be drawn by Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman and that would reflect nothing more than political bias if it were drawn. It would also suggest they do not understand even the simplest of data-driven models.

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman further cite Oklahoma Tax Commission data that they suggest captures the ‘actual’ sales and use tax payments related to the oil and gas industry, and that these data indicate that our estimates are inflated. It would be nice if the use of economic data were always so straightforward, but there are several deep problems with their use of the data. I’ll begin with four very important issues they neglect to explain to readers. First, the data they are using from the Tax Commission is not complete in that it describes sales and use taxes ‘collected’ by firms but does not fully account for sales and use taxes ‘paid.’ We believe both are highly relevant to the overall calculation of taxes paid. This is an important distinction. The oil and gas industry in the state collects sales and use taxes from customers and then remits them to the Tax Commission. This is what Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman suggest they are showing. The industry also pays sales and use taxes to other firms as part of doing business, which is then remitted by these firms. Data describing payments ‘by’ the industry are not available in any public form and must be estimated or collected in survey data from oil and gas firms. We do both in forming estimates. We also use data from publicly available economic models like the IMPLAN input-output model and the REMI model to determine whether we are consistent with their underlying estimates. Why do we do this? Because there is no complete ‘actual’ data.

The second issue is that they claim the data they provide captures the full oil and gas industry. First, the numbers reported by Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman reflect the narrow view of the data as reported in a simple report of tax receipts capturing only mining-related NAICS industry codes. You might think this would provide all you need to know about the oil and gas industry. However, the underlying and hidden problem here is that NAICS industry-level reporting based solely on the mining sector provides an incomplete view, at best, of direct oil and gas activity. Several sectors that are widely viewed as being a direct component of the state’s oil and gas industry are not tracked as part of the mining sector. There is simply no generally accepted or widely used NAICS-based definition of the oil and gas industry that can be used with the sales and use tax data because the industry’s activities spill outside the neat confines of the NAICS industry structure. Choosing a set of industries that are closely related to the oil and gas industry requires careful judgment. We comb through the details of the oil and gas sales and use tax database and examine each industry to determine if it should be considered a direct component of the oil and gas industry. For example, we include oil and gas machinery and equipment in the calculation of sales and use taxes paid by the industry. Is that an overstatement? We don’t think so. We include other highly related industries as well. The approach we prefer to use is to determine which industries have both a logical direct connection to the oil and gas industry and have data that is highly correlated with other known oil and gas sectors. They are simply misleading their readers by suggesting that the data they provide captures the full direct sales and use tax attributable to the oil and gas industry. A careful review of the sales and use tax data make two things abundantly clear. First, the industry reporting structure used by the Tax Commission cannot neatly capture payments attributable to the oil and gas industry as suggested, and that simply using components of the NAICS mining category is wholly inadequate. It has long been a point of debate exactly what constitutes oil and gas industry activity, but the numbers provided by Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman bring nothing new, or helpful, to the debate.

Third, they only list sales taxes at the state level and do not account for sales taxes paid locally. Whatever the correct number may be, the local component is roughly as large as the state figure. Which means they, at best, understate them by half.

Fourth, we maintain the full online sales and use tax database that is made available to the public and that Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman suggest they are using. We are unable to match any of the industry-level estimates they provide and cannot come close to matching most of their estimates. Yet again, another illustration of why we chuckle a bit when someone confidently touts ‘accurate’ or ‘actual’ data.

One final illustration may help illustrate how poorly the data provided by Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman capture the sales and use tax contributions of the industry. Recent surveys of state producers indicate that they currently pay about $98,000 in state and local sales and use tax per well with a 5,000 foot lateral drilled in the STACK formation. If the state rig count averages about 125 rigs on average in 2017 (our current forecast) and each rig completes 18 wells per year (based on the same producer survey data) for a total of 2,250 wells per year, total sales and use tax paid in 2017 will equal an estimated $220.5 million. And that is just from drilling activity of oil and gas firms. Between 2011 and 2014, the state’s oil and gas industry drilled an annual average of approximately 3,000 wells. If you average 2014 (a very strong year) with the sharply down year of 2015, you get 2,500 wells per year. Our estimates suggest that a ‘typical’ well back in 2015 cost approximately $5 million to drill. If you simply scale current tax payments to match the lower cost of the well back in 2015, you get about $70,000 per well in sales and use taxes in the 2014/15 period. If you don’t like the 5/7ths assumption, cut it in half. It doesn’t matter much in making the point. So, if you assume 2,500 wells drilled at a cost of $5 million per well that generates $78,000 in sales and use tax per well, you get $195 million in sales and use taxes at the state and local level. And, again, this is only the tax from drilling and excludes other activities of these firms. Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman give the industry credit for something less than $40 million using their simple look at the data. I hope this gives you a better feel for how difficult it is to simply use raw public data sets to draw conclusions about state tax policy. I also hope it gives you a feel for how costly drilling is, as well as the amount of sales and use tax revenue generated in the process.

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman further suggest that our overall estimates are ‘dramatically overstated’ as estimates of the total tax revenue paid by the industry. Because we are genuinely interested in knowing what the best estimate actually is, we take three additional steps in forming both component and overall estimates of tax payments made by the industry in order to assure the ‘reasonableness’ of the numbers. First, and most importantly, we only provide estimates of ‘direct’ tax payments and do not include estimates of spillover tax payments in the broader state economy, as is commonly done. Surely, if we were hoping to overstate the impact of the industry we would instead use an estimate that includes possible spillover tax effects. Second, to test for reasonableness, we evaluate the overall estimates using publicly available economic models like the IMPLAN input-output model and the REMI model to assure we are consistent with their underlying estimates, or can at least explain the differences. Our estimates of direct tax payments are almost uniformly lower than estimates provided by both widely-used models. Third, we compare our estimates to Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates of total taxes paid by the mining sector on production and imports (and after subsidies are accounted for). BEA’s estimates range between $2.8 billion and $3.0 billion the past five years, well above our estimate of $2.55 billion. The BEA estimate is more comprehensive and on slightly different accounting terms, but nonetheless, provides a feel for the magnitude of the total tax payments made by the industry.

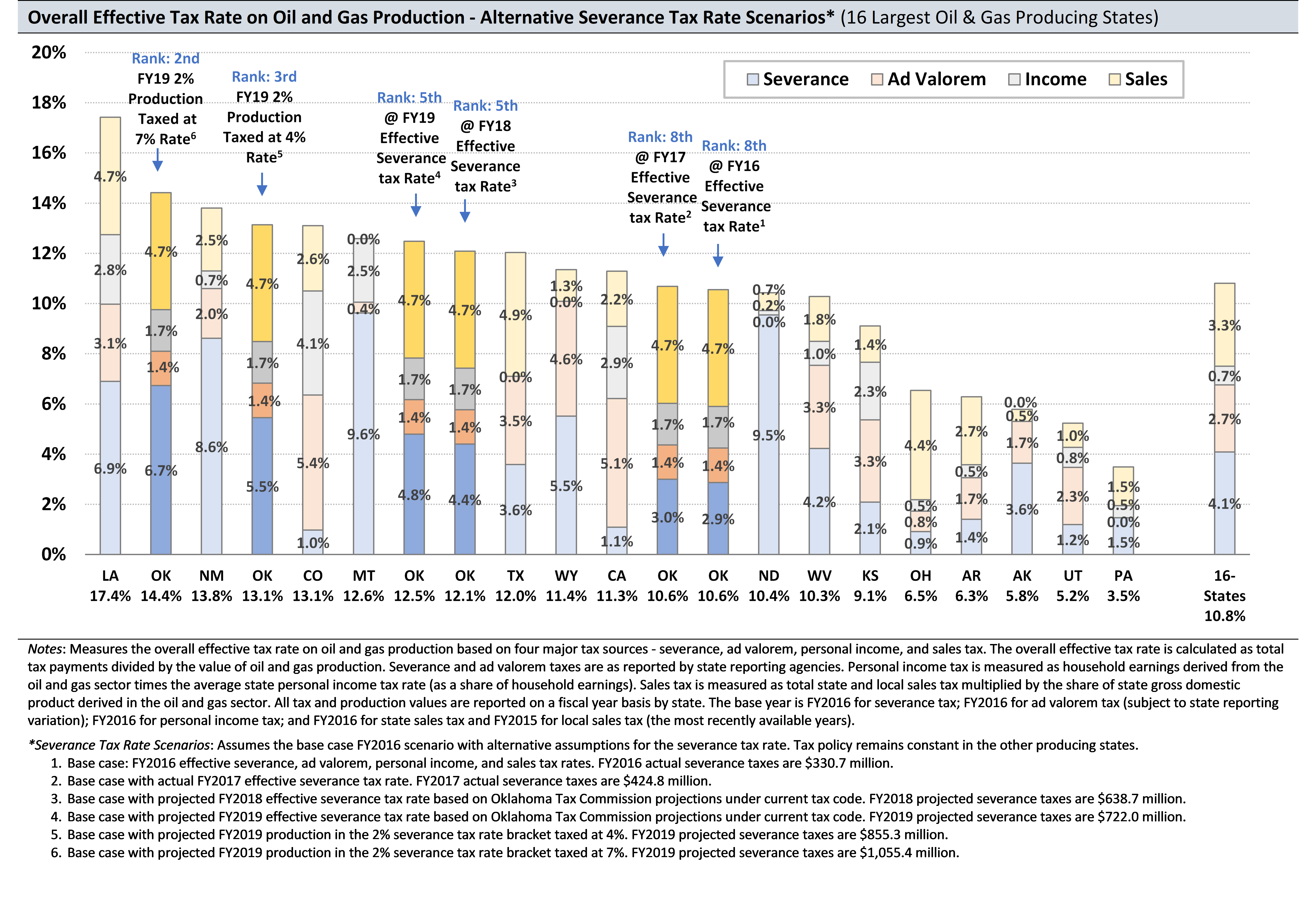

What Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman fail to offer is an alternative estimate of what they believe the oil and gas industry’s tax burden really is. Is it higher at $2.8 billion? Is it $2.4 billion? Even $2.0 billion? A bit of analysis is always far more persuasive and helpful than political grandstanding. In short, we believe that their comments concerning our estimate of $2.55 billion in direct tax payments by the Oklahoma oil and gas industry in FY2015 are of no help to policymakers. The total tax payments made by the industry changes every year, and every year better data become available for forming revised estimates – much like the corporate income tax data. As we stated in the report, it would be misleading to use numbers from recent peak years when severance tax payments alone exceeded $1 billion annually because it would almost assuredly distort the overall conclusion. And it would further weaken the argument made by Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman that the industry isn’t paying its fair share. Hence, we used the more recent and highly typical year of FY2015.

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman go even further and suggest that some of the tax payments attributed to the industry are ‘unrelated’ tax payments. For example, they suggest that payments by the industry to the state for the Energy Resources Revolving Fund and Marginal Wells fund are unrelated to the question at hand and should not be considered tax burdens. In short, they feel the oil and gas industry should receive no credit for contributions made to state revenue simply because they do so voluntarily. In short, we simply disagree. A more relevant question is whether these taxes would be paid if the state had no oil and gas industry. The answer is no.

They also feel that the $92 million in revenue forwarded by the State Land Office to the state budget should not be considered as state tax revenue tied to the oil and gas industry. This is revenue collected directly from oil and gas industry operators who operate and service wells on behalf of the state and make required payments to the state for access to land and on production. In short, we disagree with this narrow assessment. The relevant question is whether this revenue would be paid if the state had no oil and gas industry. The answer is no.

In short, the centerpiece of their post is that “Many of the figures in the report can be easily disputed with actual data or can be shown to be not true tax payments.” What they have really demonstrated is four things: 1) ‘actual’ data is not always ‘actual’ data, 2) the process of in-depth economic research is difficult and painstaking, 3) taking a quick and dirty look at data rarely reveals the true story, and 4) it has never been more important that state policymakers have access to non-politically motivated economic research. In short, the Devil is in the detail. In fact, the only potentially helpful criticism offered by their blog post is spotting an addition typo in a data table that we have long known about but changes no conclusions in the report.

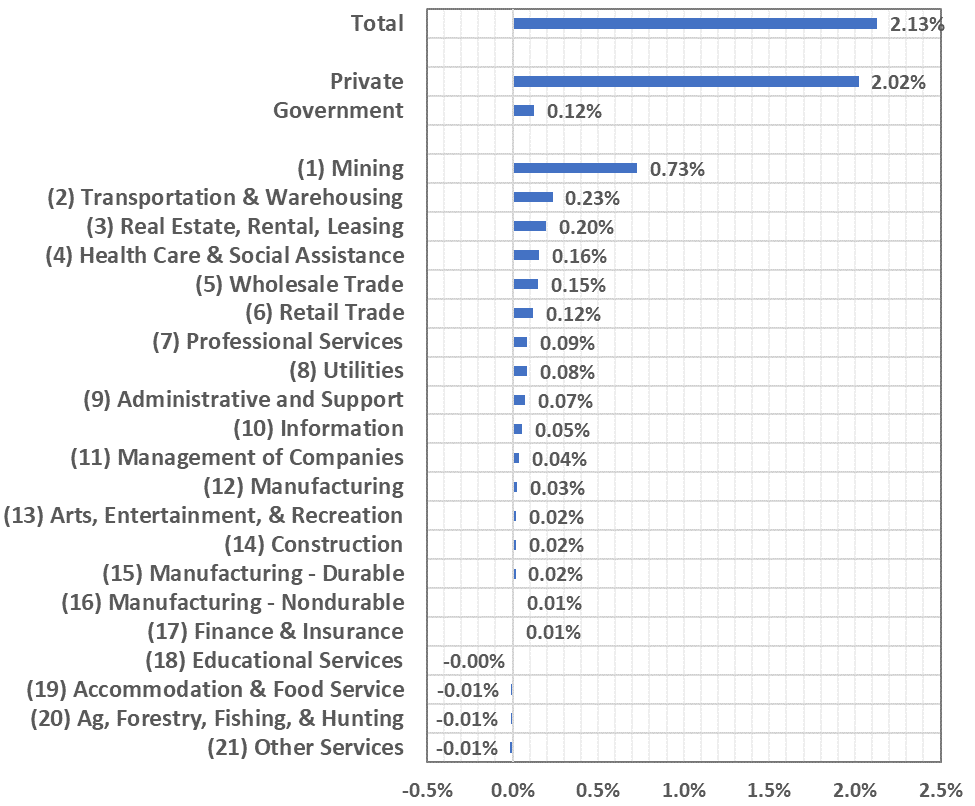

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman also provide a discussion of the historical role and legitimacy of severance taxes on oil and gas production. We have no real disagreement here. However, they further criticize our evaluation of average severance tax rates wherein we do not include ad valorem taxes to the calculation. This criticism is somewhat remarking the obvious given that ad valorem taxes are not assessed on the value of oil and gas production in Oklahoma and were not essential to and did not aid our calculations. We encourage all researchers to take up any of the issues we addressed in more depth, as well as those outside the scope of our report. However, what Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman really seem to be complaining about is that we did not set the scope of the study and prepare the data in such a way that it would make it easier for them to criticize the oil and gas industry. We view that as being completely unbalanced in performing economic analysis.

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman offer a final criticism suggesting that “Other items, such as sales taxes paid by employees on their personal purchases and the income tax these employees pay on their individual wages, are not generally counted as part of the measured tax burden of an industry.” However, this is precisely what is so interesting about the oil and gas industry given just how high these tax payments are compared to almost all other industry sectors. While they refer to employment and employee income and spending as immaterial, in our view it is one of the single most important dimensions of the oil and gas industry from an economic point of view. Even more important is that other major producing states including Texas and Wyoming have no personal income tax. When the oil and gas industry expands rapidly, the tax coffers of these states receive no direct boost from the added hiring and income earned by wage and salary workers and the self-employed in the oil and gas industry. Oklahoma, on the other hand, receives a significant boost. Any measure of the total tax burden on the oil and gas industry must take into account the role of personal income taxes paid by oil and gas industry employees and the self-employed.

What they did not comment on is a section of the report that shows another high-level approach to answering the broader question concerning the relative taxes paid by the industry and its employees. We create a scenario with the assumption that the oil and gas industry instead pays taxes at the same rate as all the remaining industries in the state economy and then evaluate the difference.

Our conclusion is: “In short, if the oil and gas industry paid taxes at approximately the same rate as the remainder of the state economy, total state tax revenue in FY2015 would decline by an estimated $1.2 billion. This represents 12.8% of the $9.29 billion in total tax revenue received by the state in FY2015. While errors are possible in any of the component calculations, the overall estimated change in tax revenue is believed to represent a useful view of the comparatively high tax contributions of the industry. In other words, primarily due to taxes unique to the oil and gas industry, high wages among proprietors and employees, and high corporate tax payments, the oil and gas industry pays more than $1 billion annually in additional state taxes than it otherwise would if it were simply an average tax-paying industry.” As we clearly state, errors are possible in any of the component calculations, but we believe the overall estimate is highly useful in demonstrating the relative tax burden of the industry. We also believe policymakers need to know this when deliberating state tax policy.

Finally, we haven’t even broached the subject of other taxes paid by the oil and gas industry such as motor vehicle taxes, motor fuel taxes, and so on, that are substantial but were left out of the analysis in order to provide a more conservative view of the industry. These taxes are substantial as well.

What is needed in this policy debate is a much more detailed view of the full tax burden paid by the oil and gas industry across the major producing states. Which is what we have worked toward for years. Not a selective view. The approach to taxation varies widely and the channels of influence can be quite different across the states. We have taken a clear attempt to estimate a useful estimate for Oklahoma, but it needs to be widened to more states and evaluated with common assumptions before any conclusions can be reached regarding the relative taxation of the oil and gas industry in Oklahoma. I encourage state policymakers to review our entire report in detail to determine whether we provide a comprehensive and balanced view of the oil and gas industry and its contribution to the Oklahoma economy.

I’ll conclude by saying that RegionTrack does not advocate for policy initiatives, and our economists have a highly visible track record of providing balanced research to policymakers. We encourage a review of our past work, particularly as it relates to the oil and gas sector. It might also be helpful for policymakers to ask Mr. Johnson and Mr. Clingman to provide a list of their past research projects where they have undertaken a detailed effort to evaluate an individual industry and its economic contributions as well as examples of their research on the oil and gas industry. We can’t find a single example.

Mark C. Snead, Ph.D.

President and Economist

RegionTrack Inc.

mark.snead@regiontrack.com